We know that to avoid a climate meltdown our lifestyles must change; emitting less CO2 and other gases that warm the earth’s atmosphere. But how can we do this quickly and cheaply? Contrary to what is often said, this is not the only technical progress that will take us forward. Our behaviour as individuals and in industry is largely responsible for the climate problem.

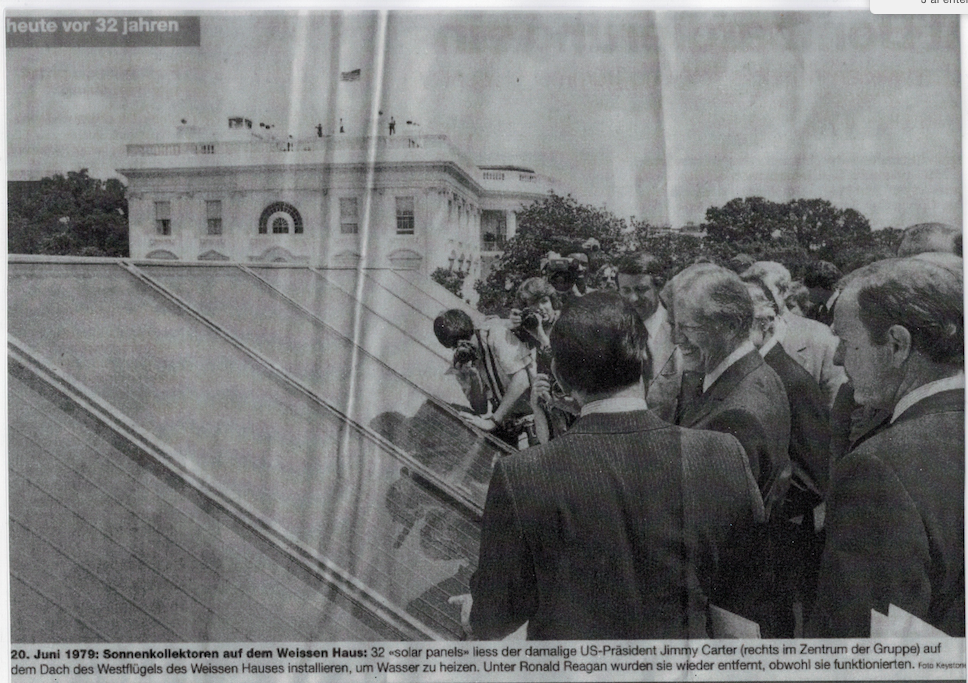

The concept of energy sobriety is not new. In the post-war years and the years following the two oil crises, people used to talk about saving energy or searching for waste. However, we still live in a world of energy drunkenness and we don’t even realise it any more: vehicles that are oversized for our purposes, too many journeys, ever larger homes, too much food… all are part of daily life for many of us. Unfortunately, energy at all its stages (extraction, refining, combustion, etc.) and in all its uses (domestic, agricultural, industrial, etc.) is the main cause of CO2(1) emissions and in Western countries it became abundant and cheap. The waste chasing has gone out of fashion. In 1990, Amory Lovins, an American scientist and founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute, wanted to give the term ‘energy saving’ a new lease on life and created the word negaWatt(2). The basic idea is simple: we don’t need to produce extra Megawatts, we need to apprehend negaWatts.

Author

Philippe Bovet

Journalist, president of negaWatt Switzerland.

About

negaWatts

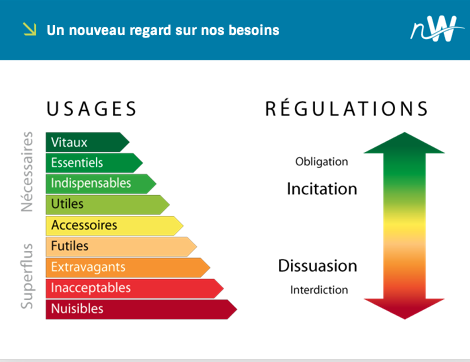

But where to find these negaWatts? You may be somewhat familiar with the two concepts of energy sobriety and energy efficiency. Sobriety corresponds to the choices we consciously make. It’s the volume of the fridge I buy, the temperature at which I heat my flat or cool my office, the size of the car I’m going to buy and the distances I’m going to travel with it, etc. The bigger the volume, the greater the action and the more energy I’m going to consume and the worse my CO2 footprint will be. All the choices that I make correspond to the active part of my energy transition. Efficiency, on the other hand, is synonymous with the best technique of the moment. It is the A +++ label for a refrigerator, the hybrid motorisation of a car, etc. It is the passive part of the energy transition, because once the size of the object is chosen, the technique does the rest.

Nothing to do with renunciation

The combination of sobriety and efficiency – i.e. the size of the object and its technical quality – results in a significant reduction in energy consumption. Let’s say I have to change my fridge. Having understood the value of my personal choices, I think about my real needs. I tell myself that I could go to the market more often to buy fresh vegetables, have more dry goods in my cupboards and consume less frozen food. So, I switch to a smaller model and use the most energy efficient one at the moment. In terms of food refrigeration, I won on two counts: sobriety and efficiency. The same can be said for cars. Do I have to change my vehicle? I think about my needs and I choose a smaller vehicle with a hybrid engine. If I intend to move, why not find a home closer to my work, in order to reduce my kilometres driven, ask myself whether my car is still necessary and, if not, replace it with public transport and car-sharing, which I can manage via mobile applications.

Sobriety in this context is synonymous with common sense and therefore has nothing to do with renunciation. We are not asked to give up cars or planes, but we must use these tools for their real qualities. The plane is made for long distance, not for a Geneva-Paris trip that can be done by train. A car may be necessary for some journeys but driving a 4×4 of almost 2 tons capable of reaching 200 km/h, while our road network allows a maximum of 120 km/h, is not acceptable in times of global warming. We must not give up holidays, we must only change their nature, i.e. stay closer and without having to resort to air travel.

Sobriety is not linked to a life of constraint; this is not a former smoker who must refrain every day from going to buy a cigarette. Moreover, it can be linked to information technologies that make our daily lives easier while encouraging the development of a society of services and sharing (Mobility) rather than promoting even more unbridled consumption (Amazon).

A new deal

It is estimated that sobriety would reduce energy consumption by at least 30% and efficiency by more than 20%. The rest of the needs are therefore easily covered by renewable energy sources. This makes the energy transition simpler and cheaper. Over the last few decades we have learned to squeeze a PET bottle before recycling it, to no longer smoke in cafés and restaurants, to put on a seatbelt when getting into a car, to use a new letter of the alphabet namely @, etc. Would we not be able to assimilate this new deal and produce negaWatts? Admit then that this sobriety that costs nothing – except a more thoughtful awareness of our choices and the information campaigns that the federal authorities must carry out more actively – must earn its letters of approval.

(1) Here I am talking mainly about fossil fuels. Renewable energies have a low CO2 ‘weight’, even if they sometimes have an impact. Between fossil and renewable energies, we must choose the energy solutions that emit the least.

(2) Here is his 1990 article: https://rmi.org/insight/negawatt-revolution/. He is also one of the three authors of the book ‘Facteur 4’ (published in 1997 in fr. – ed. Terre Vivante).

The author

Philippe Bovet

President of negaWatt Switzerland, swiss-french journalist specialised in energy and environment, and living in Basel.

Philippe Bovet has been a freelance journalist since 1989 and has specialised in energy and the environment for fifteen years. When he lived in Paris in the 13th district, he became involved in a ZAC (concerted development zone) project by creating the Association des Amis de l’EcoZAC. By way of persuasion and information, the small group of about ten people won their case. From this undertaking the first eco-neighbourhood in Paris was born.

His years of reporting have also led him to write two books. The first is devoted to Eco-neighbourhoods in Europe. The second is about exemplary buildings in France. It is not so much about constructive techniques, but above all about human engagement, i.e. portraits of people who have understood that our energy system needs to change. They then went into practice through committed and worthwhile projects.